When it comes to choosing the correct way to store your video archive, there are a lot of factors to consider. One of those factors is Chroma Subsampling. A lot of places on the Internet will recommend 4:2:2 because it is said to be great enough to encapsulate the limited colour properties contained within analog sources. However what I have never seen discussed is generational loss. I got to wondering, as we connect multiple pieces of equipment together in a chain and then also process through software editing, all of which do Chroma Subsampling, is there any generational loss when doing this? I set off to find out.

Consider the following:

You have an original VHS tape with it’s included analog reduced chroma signaling that connects to a Capture Device with Chroma Subsampling at 4:2:2 which stores in a Captured File with Chroma Subsampling of 4:2:2 which you then edit and perform a hopefully final export with it’s own Chroma Subsampling, again at 4:2:2. Thats four conversions, (or potentially reductions) in colour information as a minimum starting point. You’ll note I said reductions, not an exactly correct phrase, but my suspicion is it’s more correct than saying ‘if you keep 4:2:2 it will maintain quality because VHS doesn’t have much to begin with’. I would say the opposite, ‘if it’s low to begin with why would you want to make it worse?!’

Side note: This method is also used in compression technology for still images such as jpeg.

What is Chroma Subsampling anyway?

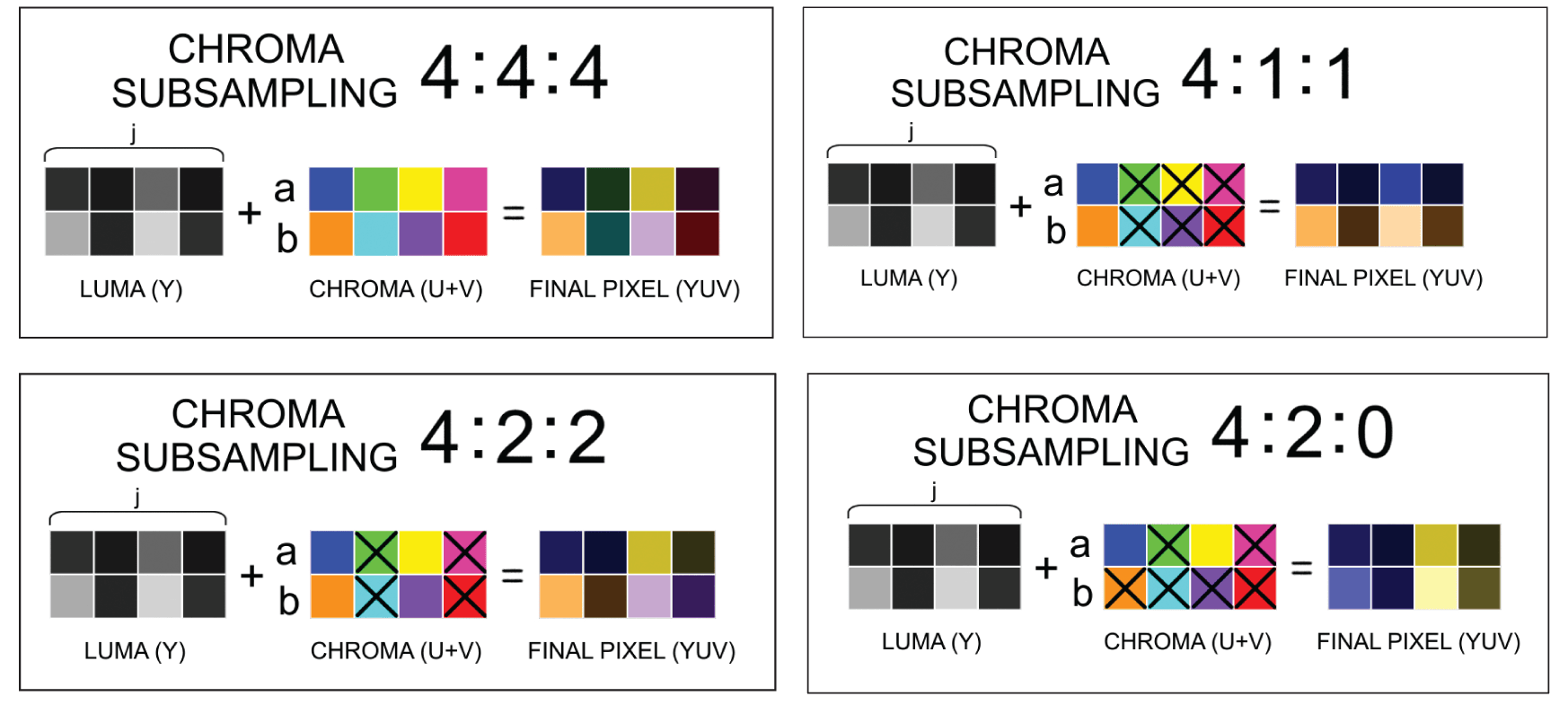

In simple terms, chroma subsampling is a process used to reduced storage requirements and bandwidth requirements for video data by reducing the colour information stored in video file or transmitted in a video stream. This can and does save a lot of space. It works because the luminance data (the black-and-white part) is more important to the human eye and thus Chroma subsampling effectively leaves this part intact / as is. The Chroma part however (chroma refers to the colour information), is not quite as important to the human eye and thus the theory is we can reduce the accuracy of this information because we’re unlikely to notice a difference unless comparing side-by-side, before and after – exactly what we are going to do here.

The analog Chroma Subsampling method

VHS already uses a form of subsampling by reducing signal bandwidth in the analog domain, however this is not the same thing exactly as chroma subsampling in the digital domain. But for the purpose of choosing an archival codec, it is worth mentioning that VHS by its nature already reduces the colour signal quite a bit before we even get a chance to capture it with a modern codec. If interested, Wikipedia has some great articles on how this works on analog systems, such as this one.

As shown above, it’s also important to know that before we even get to storing video data in a file, not only has the analog domain reduced the colour information through signal bandwidth optimisation but the capturing device has also subsampled it as well and you can never ever get this colour information back. How bad this is, depends on what your capture card is, which colour system you use and a number of other factors. But from a subsumpling perspective the likely worst will be 4:1:1 for NTSC and 4:2:0 for PAL.

How much you care about this will depend how much of an archivist you are and the future workflow likely to take place after the video is captured. But most likely by the time you are storing it in a file, you have already suffered three generations of loss (one you can’t control, one you can control only partially through selection of capture device and one you can usually control, the capture file. If you’re like me you won’t want to lose any more colour information than necessary because you will realise there will usually be further activities like editing and exporting to come resulting in even further loss. It is also entirely plausible depending on your workflow that additional losses will be incurred if you can not process all adjustments for the entire workflow directly from the master file.

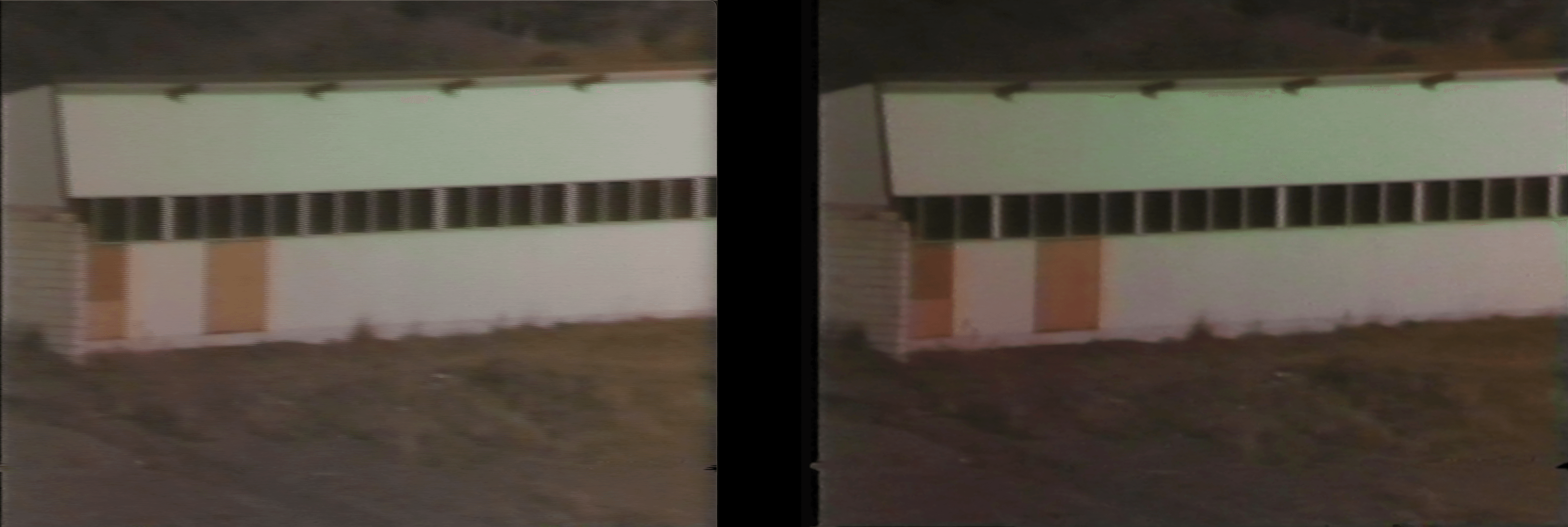

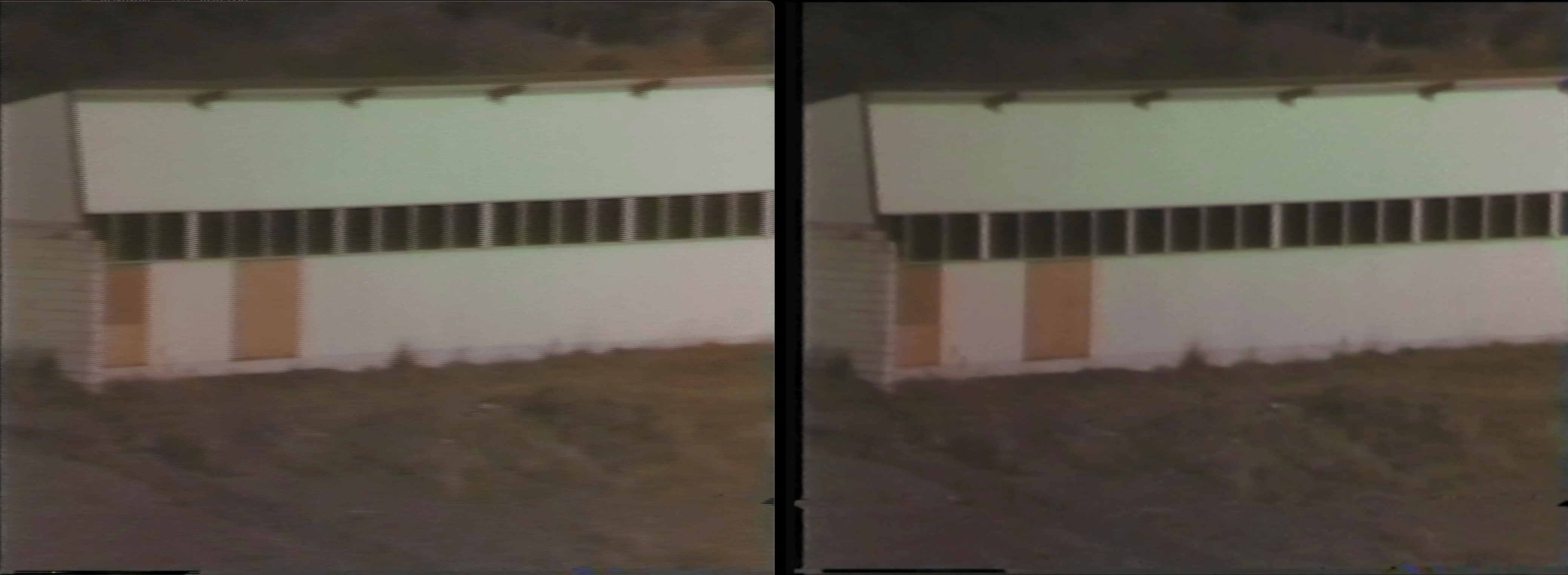

It is worth noting that when your source video is of a high resolution (such as modern digital video cameras at 1080p and above) the subsampling issue is far less prevalent simply due to the visibility (or invisibility) of much smaller pixels to apply losses to. However with VHS being of a lower resolution, particularly in the US and countries that use NTSC with it’s meagre 480i resolution, the effects become quite noticeable quite quickly. You can test this yourself by re-encoding some source footage with contrasty areas up to 4 times and look at the difference, two examples are shown below.

The below compares a consumer analog PAL 576i VHS source with four generations of exports, in the first 4:2:2 example you can clearly see the loss of colour, colour bleed around edges and blending of colour into areas it’s not supposed to be (click to zoom in for more detail). Whereas in the second 4:4:4 example this is basically non-existent.

Let’s take a closer look at the relevant chroma subsampling ratios

4:4:4 Chroma Subsampling

With 4:4:4 chroma subsampling, there is no loss of colour information because each pixel retains its own unique color information. This means that the color resolution is equal to the luminance resolution, resulting in a higher level of detail and color accuracy. Videos encoded at 4:4:4 chroma subsampling are often used in professional applications where color fidelity is crucial, such as video editing or color grading.

While 4:4:4 chroma subsampling provides the highest level of color accuracy, it also requires the most data to be stored and transmitted. This will result in larger file sizes and increased bandwidth requirements.

4:2:2 Chroma Subsampling

In a 4:2:2 chroma subsampling, there is a 50% loss of colour information. For every four pixels, two pixels share the same color information. This means that the color information is sampled at half the resolution of the luminance information. While this ratio is widely used and provides good image quality, it may not be ideal for certain use cases such as archiving. This is the better of the two fairly typical subsampling rate in PAL and NTSC sources.

4:2:0 Chroma Subsampling

4:2:0 chroma subsampling loses 75% of the colour information. For every four pixels of colour, three share the same colour information as the first. This is unfortunately another fairly typical PAL Chroma Subsampling rate.

4:1:1 Chroma Subsampling

4:1:1 chroma subsampling also loses 75% of the colour information. However if you look at the diagram above you will see the samples are taken from both the a row and the b row, whereas 4:2:0 takes samples from just the a row. For analog capturing purposes 4:1:1 is used in NTSC formats. Whether 4:2:0 or 4:1:1 is better has been a topic of hot debate. Tip, many of the capture cards use 4:1:1 or 4:2:0, so make sure you check yours to make sure you’re not losing 75% of your colour information.

Conclusion

In my opinion, understanding the difference between the various types of chroma subsampling ratios is essential to avoid later disappointment down the track. The last thing I would want after spending days, weeks, months, or even years archiving precious analog sources, is to discover I used the wrong chroma subsampling just to save a little disk space and find out the only solution to fix this, is to start again. It seems clear to me at least that Chroma Subsampling generational loss is indeed real, but feel free to do your own test and comment in the forums if you disagree.

If your capture source is VHS it is already known for its imperfections, including noise and colour bleeding. When encoding at 4:2:2, these imperfections will amplify with each device or step in the chain.

While 4:2:2 offers good image quality and is widely used, I couldn’t recommend it where colour accuracy is paramount, because as shown above, 4:2:2 is literally the process of removing colour information, form your painstakingly captured sources. As shown, this is more obvious when dealing with lower resolution standard definition sources (480i / 576i). In such cases, starting by creating a 4:4:4 master can help preserve the highest level of colour information, so you can be sure you have the best looking image you can have and won’t have to go back and capture everything again to get it.

Of course, you may not think it matters enough and that choice is entirely up to you.

For capturing methods that include a 4:4:4 capture method, please see our capturing guides here.